According to a recent consumer study, durability is one of the most-important factors when choosing a wood flooring option. Durability is tied to hardness. From the consumer’s perspective, it is asking a question such as, “If I were to drop a can of soup on the wood floor, how much damage will it cause?” The short and simple answer is that a softer species of wood flooring will indent deeper than a harder species of wood flooring would.

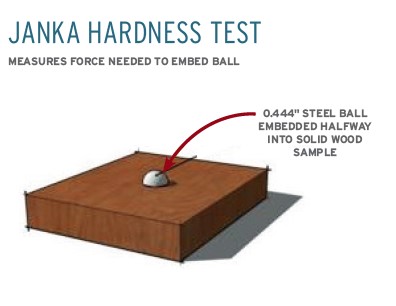

The wood flooring industry historically has identified wood species by the physical and mechanical properties they exhibit. One of those characteristics often referred to is the hardness of the wood itself. We commonly refer to this characteristic as “Janka Hardness.”

(1864-1932)

The Janka hardness test was named after Gabriel Janka, an Austrian wood researcher. In 1906, he developed a modified Brinell hardness test (which is used for testing the hardness of metals) that also could be used for testing the hardness of wood. This test method officially was adopted by the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) in 1927.

ASTM D143 is a test method that helps us determine how hard a species of wood is. This test method is the standard test method for small clear specimens of timber. This standard represents different procedures for evaluating several mechanical and physical properties of wood, including the hardness test. This test involves measuring the force (in pounds) required to embed a steel ball with a diameter of .444” to half its diameter into the wood sample.

As with all ASTM test methods, there are specific parameters required to ensure consistency in the results. According to ASTM D143, the size of this steel ball was chosen as it corresponds in metric terms to an area of circular indentation equal to 1 cm². The wood sample should be 6” long, and 2” by 2” in size. There is also a secondary method that utilizes a 1” by 1” cross-section, which is used more commonly when testing solid ¾” wood flooring. The size of the sample is important for many reasons.

- It is influenced by the number of growth rings in the sample.

- It is less influenced by the earlywood and latewood differences than smaller size specimens.

- It is large enough to represent a considerable portion of the sampled material.

This test is conducted twice on the radial face (quartersawn), and twice on the tangential face (plainsawn). The results of these tests are averaged to give an assessment of the sample. This value only represents the individual piece that was tested. The numbers we use in our charts are derived by averaging a large sampling of tests from the same species. This assessment value is referred to as the Janka value for the species. This is what we use to qualify the hardness of a solid wood flooring product.

What about engineered wood flooring? When relating Janka information to engineered wood flooring, it is inaccurate to claim the same hardness properties as its solid counterpart. So why are we so reliant on these numbers?

Here is where the rubber hits the road. Every engineered wood floor product has its own physical and mechanical properties, including its hardness qualities. In some cases, the engineered floor may be harder than its solid wood counterpart; in other cases, it may be softer (dependent upon many factors, including the thickness of the wear layer and the type of core material).

There is a separate test method that gives direction to test the hardness of many engineered wood flooring products. ASTM D1037 is a similar test method to ASTM D143, but it is used for wood-based fiber and particle panel materials rather than solid wood. This test requires different sized samples (3” by 6” and 1” thick) and incorporates the same measurement of force required to embed the same steel ball with a diameter of .444” to half its diameter into the sample. The results of this test are very specific to the product being tested.

Some engineered wood flooring manufacturers have gone as far as to have these tests performed on many of their engineered flooring products in an effort to provide some real information that can help the end-user make an educated buying decision based on a hardness value.

There is a third ASTM test that more directly applies to our industry, and also answers the question, “If I were to drop a can of soup on the wood floor, how much damage will it cause?” This is spelled out in ASTM D2394, also known as the “Falling-Ball Indentation” test. This is an impact test, so it’s mimicking the act of dropping something small but heavy onto the floor from various heights, and measuring how finished wood and wood-based flooring products resist impacts from the dropped objects.

This test involves dropping a 2” diameter, 1.18 lb steel ball onto the flooring at 6” increments, up to 72”. The depth of indentation after each drop is then recorded and plotted against its associated drop height to get a curve of indentation. Like Janka, it can be an excellent comparison test; the max indentation depth and slope of the indentation curve can tell you a lot about how products perform across lines, or how they compare to other products. Industry laboratories, such as Capital Testing (formerly HPVA Laboratories), are capable of running these tests.

Unfortunately, many sales professionals oversell the hardness of the flooring, and inaccurately use the published solid wood Janka rating for all types of wood floors. These performance characteristics have become a driving point for how the consumer will be influenced on their flooring selection.

The durability and hardness of a floor can be a powerful tool when choosing flooring for a home. When people want a wood floor, the longevity and durability factors should drive selling the value of real wood.

Where this becomes a major concern is when performance comes into consideration. Consider a homeowner shopping for a new wood floor who has a very active house with large dogs. The sales professional decides to sell them the hardest species that they carry (Ipe, with an average Janka rating of 3680), based on their active home and lifestyle. Then the conversation turns to whether to sell them solid wood or engineered wood. The sales professional decides to sell them an engineered Ipe floor, based on a few factors they discovered in their discussion with the customer. Due to pricing constraints, the homeowner ended up purchasing a flooring product that has a thinner wear layer (1.5 mm).

Fast-forward three months after installation. The customer is upset that their floor is denting too easily.

This floor was sold based on the hardness of Ipe, knowing that the consumer had a very active house with large dogs. The actual hardness of this flooring product was considerably less than what they were sold, and they ended up disappointed in their new hardwood floor. The unfortunate result in this scenario is that the floor ended up getting torn out and replaced with another floor.

The problem seems clear and avoidable to those of us in the industry. Unfortunately, it is not as clear to the homeowner or to the uneducated sales professional who influenced the homeowner to purchase a specific floor. The ability of a sales professional to influence the buyer to choose one product over another is often the point where a successful floor, or a failure, begins.

The durability and hardness of a floor can be a powerful tool when choosing flooring for a home. When people want a wood floor, the longevity and durability factors should drive selling the value of real wood. Understanding that ALL wood floors will dent when a can of soup is dropped on them, is also knowing the truth behind what it is we work with every day. Try thinking of the dent as a mark in time.

Brett Miller is the vice president of technical standards, training, and certification for the National Wood Flooring Association. He can be reached at brett.miller@nwfa.org.